The History of a Letter

By Dr. Klerman Wanderly Lopes

Introduction

The so-called War of Secession of the United States, between 1861

and 1865, pitted 11 Confederate States of the South, whose largely

agricultural production was based on the work of slaves originating

from Africa, against the States of the North, which was already

quite industrialized. The war, which cost the lives of close to

970,000 people (about 3% of the U.S. population at the time)

involved an enormous consumption of metals for the manufacture of

weapons. Besides the war itself, the high cost of metals also

affected the postal services, leading the authorities to encourage

the payment of postage with coins, charging a higher rate for fees

paid with paper money. This dual fee regime persisted for many years

after the end of the conflict. To illustrate this postal curiosity,

we present an interesting letter in which this differentiated fee

was applied.

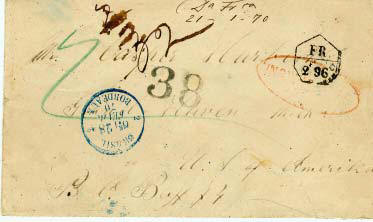

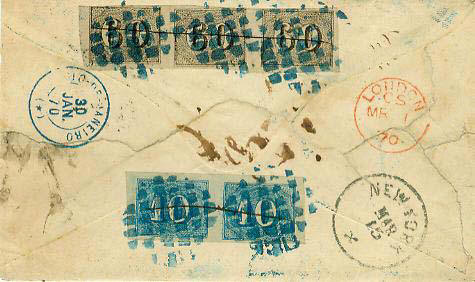

Presentation of the philatelic piece

Front

Back

Description

Letter from Rio de Janeiro to the United States, of January 30,

1870, transported by the ship Amazone, of the French “Messageries

Impériales”. It was franked with 200 réis in Brazilian stamps, an

amount insufficient for the payment of the simple fee in force at

the time of 540 réis to the United States (weight up to 7.5 grams)

for the English or French mail. Thus, the postage was considered

insufficient and the oval postmark indicating that fact was applied

to the front, subjecting the letter to full payment of the freight

charge at the destination. The Amazone landed in Bordeaux on

February 27 and the letter was received in Paris the next day. There

the letter was considered double rate or franking (weight between

7.5 and 15 grams), receiving a written notation “2”, the postmark of

entry “Brésil/2 Bordeaux 2” and the French-British exchange mark

“FR/2F 96c”. Sent to America by the English Postal Service, it

transited in London on March 1. Upon arriving in New York on March

15, the letter received the postmark with the rate of 38 cents (in

paper money) and the written notation “32,” the amount to be

reimbursed to the British and French postal services.

Additional Comment

When the letter arrived in France, the U.S.-France Convention

was no longer in force (since December 31, 1869), and the

French-British Convention was used to obtain the reimbursement for

the transport of the letter to France, seen by the mark of the

second freight charge and the exchange mark applied in Paris. The

letter was sent to New York under the conditions of the U.S.-England

Convention of January 1870. According to its terms the American

Postal Service should have paid the British Postal Service (for each

1/2 ounce of weight) 2 cents for the British transit and 2 cents for

the Trans-Atlantic transportation, in addition to the 28 cents for

the fare owed to France (double freight charge = 1 Fr 48 c).

Therefore, the total to be reimbursed to the English Postal service

was 32 cents (written on the front). In accordance with the

Convention of 1870, the American Postal Service should have

collected 2 cents for the internal distribution, making up a total

of 34 cents en payment in metal money or 38 cents in paper money.

Thanks to friend Jeffrey C. Bohn for

the comments on the American postal marks.

Copyright © 2011 Klerman Wanderly Lopes